When Japan formally surrendered on board the USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945, there still were seven million Japanese soldiers and civilians scattered throughout the Pacific and Asia with no way of returning home. The Allies had so devastated Japanese shipping during the war that few transports remained. There were some grumblings among U.S. officials who thought that it was Japan’s problem to rectify, but it was quickly recognized that after suffering under Japanese occupation for years, countries such as China and the Philippines should be relieved of the burden of stranded Japanese troops. There was also a need to return the million Chinese and Koreans who had been taken by the Japanese for slave labor.

(Imperial War Museum)

By mid-September, a plan to repatriate Japanese personnel and revive the Japanese economy began to take shape. The U.S. Navy established the Shipping Control Authority, Japanese Merchant Marine and the Japanese Repatriation Group, known collectively as SCAJAP, under the Commander, Naval Forces, Far East (COMNAVFE). RADM D. B. Beary commanded SCAJAP with RADM Charles “Swede” Momsen serving as his chief of staff. SCAJAP developed regulations for Japanese shipping rights, laws of the sea, and safety rules. SCAJAP then assembled a fleet to transport cargo and another fleet to be used for the repatriation operation.

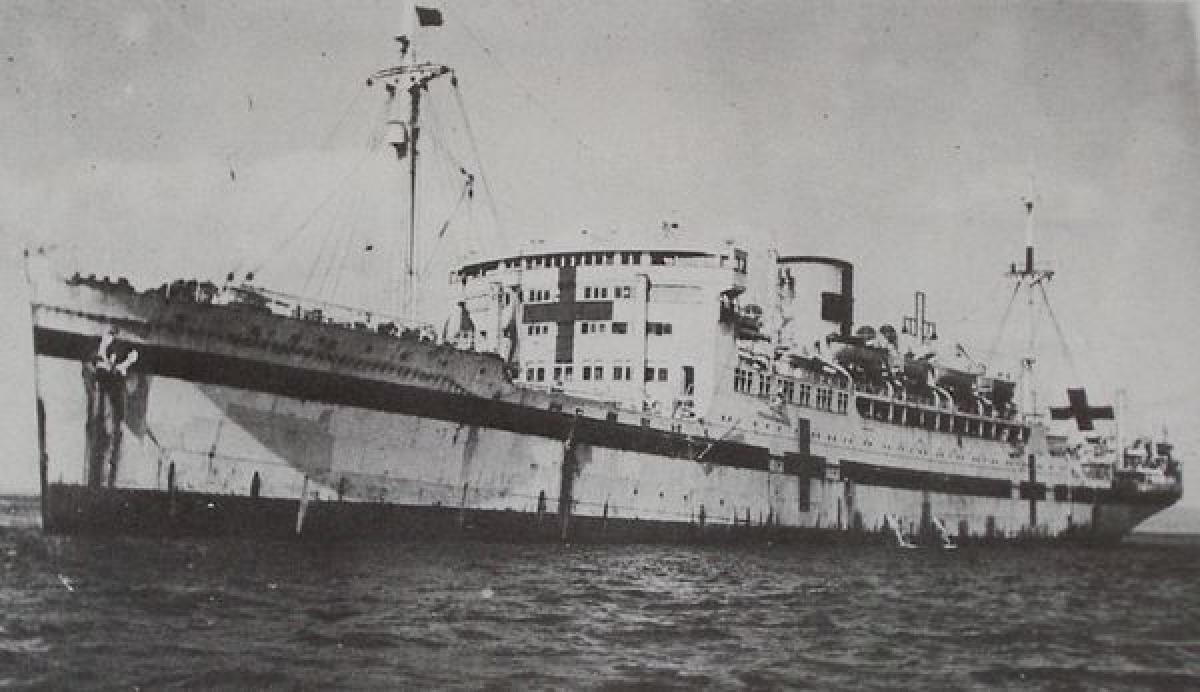

To hasten repatriation, SCAJAP gave Japan 85 LSTs and 100 Liberty ships that had been slated for decommissioning. Because the plan called for the ships to be operated by Japanese crews, all the instruments and hatches had to be remarked with Kanji. SCAJAP also repurposed any seaworthy vessel it could, including warships, for the mass repatriation effort. The Hosho and Katsuragi, among the few Japanese carriers to survive the war, were given new roles as passenger transports, as were destroyers such as the Yoizuki. The ocean liner Hikawa Maru, which had been converted into a hospital ship, was used to gather thousands of men at a time. The fleet of castoffs eventually grew to about 400 vessels. The Japanese government was responsible for providing the crew with all food and supplies. Fuel had to be bought through U.S. authorities.

(Australian War Memorial)

Because the rising sun flag was abolished following the surrender, the ships of SCAJAP were given their own flags. Japanese-owned ships with Japanese crews flew a blue and red pennant modified from international flag signal code for “Echo.” American-owned ships with Japanese crews flew a flag of red and green triangles based on the signal code for “Oscar.”

Unsurprisingly, many American servicemen who were waiting to be shipped back to the United States were not happy with the effort. They complained that their return was being delayed because resources were being used to accommodate the same Japanese whom they’d been fighting only weeks earlier. Officials explained that Asia would not recover without immediate repatriation, resulting in more Americans having to stay longer to stabilize the region.

The operation was conducted quickly and efficiently with only a few incidents. One fully laden ship sank after hitting a mine near China but only 20 of the 4,300 passengers were lost. In another incident, there was outrage when the public learned of the appalling conditions of a ship that was overcrowded with women and children being returned to Taiwan. Korean refugees on another ship almost mutinied against the Japanese crew because of what they believed was inhumane treatment.

The removal of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians on Taiwan also was problematic because many had lived on the island their entire lives and considered it their true home. Most wanted to remain, but the Chinese announced that they intended to use any Japanese on the island as slave labor. Against U.S. objections, the Chinese also created ways to extort the Japanese being repatriated by charging them for the transportation and inoculations that the United States was providing for free.

SCAJAP ships also encountered bitter feelings that remained from the war. When a couple of Japanese-operated ships pulled into Hawaii for repairs, the crew was not permitted to go ashore.

The repatriation effort was conducted at a remarkable speed. It was initially estimated that the operation would take until July 1947 to complete, but In March 1946 Momsen projected that the repatriation effort would be complete by that May, with the exception of the 1,700,000 Japanese who were being held by the Soviets. SCAJAP earned additional praise from the Japanese government for returning the exhumed remains of thousands of Japanese war dead from far-flung places.

SCAJAP’s repatriation operation was an extraordinary logistical achievement that played a significant role in the postwar recovery of Asia. After completion of the operation, SCAJAP ships would soon be called upon to transport men and equipment to Korea, providing crucial support in the amphibious operations at Inchon and Wonsan.

The signing of the Treaty of San Francisco on 8 September 1951 meant that Japanese ships could again fly the rising sun and operate under policies developed by the Japanese government. On 1 April 1952, SCAJAP was dissolved. Many Japanese-crewed ships remained in the service of Military Sea Transportation Services, drawing the ire of U.S. maritime unions, which charged that the practice was depriving Americans of jobs.