The 13 September 1759 Battle of Quebec, one of history’s epic struggles, is remembered partly because it claimed the lives of both opposing commanders: Major General James Wolfe and Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm.1 British victory led to the largest land transfer in history, as New France, the French colonies in North America, was ceded to Britain and Spain at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War.

Significantly, had the French defeated the British or retained the territory via the 1763 peace treaty, the geopolitical environment for the Thirteen Colonies would have been radically altered. With the French strongly anchored to the north and Spain occupying significant territory to the south and west, there is a strong possibility that the colonies would not have dared revolt against Britain. Hence, Wolfe’s victory precipitated the establishment of what would become the United States of America.

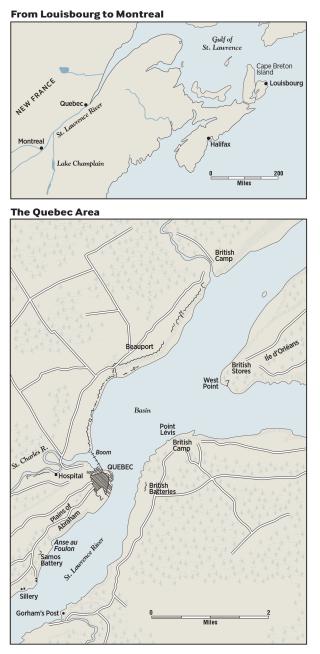

Often overlooked is the fact that Britain’s Royal Navy made the victory at Quebec possible. Close army and navy collaboration had developed during the siege and 26 July 1758 capture of the French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island at the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Rear Admiral Charles Holmes arrived at Louisbourg from Britain with soldiers, rendezvousing with British and Colonial American troops who had been serving in America. The assembled force’s commander, 32-year-old Wolfe, arrived in mid-May 1759. Its daunting assignment was to travel up the St. Lawrence River and capture the imposing fortress city of Quebec. The capital of New France, it was located at the tip of a peninsula formed by the St. Lawrence and St. Charles rivers and protected by high cliffs and stone ramparts.

Advance Up the River

The voyage from Louisbourg to Quebec City was extremely dangerous. In early June, Vice Admiral Charles Saunders, the senior Royal Navy officer present, sent some of the greatest seamen and mapmakers in maritime history, including future explorer James Cook, sailing master of the 60-gun HMS Pembroke, to pilot an advance flotilla and mark the route to Quebec with buoys.2

From the deck of his flagship, the 90-gun HMS Neptune, Saunders commanded an armada of ships across the Gulf of St. Lawrence and up the river. To the surprise of the French, by the end of June, Wolfe’s army began landing on the Île d’Orléans, just downstream from Quebec. Forty-nine warships manned by 13,500 sailors and 119 merchant vessels with about 4,500 merchant seamen safely and rapidly had transported 8,500 British soldiers, their supplies, and equipment. Twenty percent of the Royal Navy was now concentrated around Quebec, while British warships in the Atlantic guarded against a French naval expedition to relieve the fortress city. There were one and a half Royal Navy sailors for every British soldier. Importantly, British naval power had projected and secured soldiers 700 miles into enemy territory.

The navy not only supplied Wolfe’s forces during the ensuing siege but also deprived the Quebec garrison of food from downriver. To patrol and maraud upriver, Saunders ordered a flotilla to run under the guns of the fortress. On the night of 18–19 July, five warships made it through the narrow strait between Quebec and Point Lévis.3 These vessels ensured that French frigates, which had fled upstream toward Montreal, could not sail down unimpeded to attack Wolfe’s forces and/or the naval vessels. Wolfe thus could conduct a siege in a safe bubble hundreds of miles within hostile territory.

Montcalm was not prepared for his major food sources to be cut off so effectively and had to disperse 8,500 of his 16,000 men to other locations. Furthermore, the conscription of so many local men between the ages of 14 and 60 severely hampered bringing in the late summer–early fall harvest, which was needed to feed the colony. Diaries of the time indicate that the French defenders were on half rations by early September.

Often ignored is that the Royal Navy had brought 30 stackable 36-foot landing craft from Britain.4 Rowed by 20 sailors and with a ramp for embarking and disembarking 50 soldiers, the flat-bottomed boats allowed Wolfe to maneuver his troops quickly. The British increasingly dominated the region by transporting soldiers to attack enemy settlements many miles upriver and downriver from Quebec City. New France originally was settled along the St. Lawrence, and roads were relatively few and far between. The landing craft converted the colony’s river highway into a military asset to starve and isolate the fortress of Quebec.

Initial British Defeat

By the end of July, the British had established three fortified camps downriver from Quebec—at the mouth of the Montmorency River, at the southern end of the Île d’Orléans, and at Point Lévis—and one gun battery with five mortars and six cannon directly across from the fortress. These strongpoints protected the British redcoats from attack by France’s Native American allies and Montcalm’s militiamen and irregulars. Cannon and mortars continually bombarded the fortified city. In July and August the defenders countered naval attacks by sending fireships toward the British fleet; however, rowboats towed away all the incendiary vessels before any damage could be inflicted.

Wolfe’s first major attack, on 31 July, was directed against French defenses at Beauport, but it was a complete failure.5 Rocky sandbars created by the 19-foot tide prevented larger ships from approaching close to the riverbank. After boarding a landing craft, Wolfe found a suitable place for boats loaded with troops to reach the shore. Once on the beach, disorganized British soldiers charged French trenches but suffered high casualties.

After the debacle, Wolfe’s brigadiers suggested a north shore landing far upriver, west of the city. British troops then would advance on Quebec along the tabletop between the cliffs of the St. Lawrence and St. Charles rivers. But Wolfe rejected the plan, as his soldiers would be subjected to intense fire from irregulars in the brush along the way.

Meanwhile, starting near Cap Rouge, British troops transported in landing craft were destroying French supplies and villages upriver. The boats also would move upstream and downstream with the tide to tire and confuse French soldiers marching along the shore to defend against a landing. On 9 August, Montcalm dispatched Colonel Louis Antoine de Bougainville to take command of the 500 troops scattered between Quebec and Montreal. In early September, the colonel received reinforcements that brought his strength up to about 2,200 men. In a continuing effort to thwart the raids, Montcalm and Bougainville were often forced to move their troops, including elite Grenadiers, to different locations in anticipation of British forays.6

Reconnoitering the Cove

On 10 September, Wolfe and a small party that included Rear Admiral Holmes, who commanded the upriver naval force; Royal Navy Captain James Chads; and Brigadier Generals Robert Monckton and George Townshend sailed from off Cap Rouge to Gorham’s Post to spy out a new plan. From ashore they observed the Anse (Cove) au Foulon across the river, two miles upriver from Quebec.

As Wolfe would be killed during the subsequent battle, how and what he learned about the cove is uncertain. The most likely source of information about a path up the nearby cliff to the Plains of Abraham was Captain Robert Stobo.7 He had been with Colonel George Washington’s Virginia Regiment at the Battle of Fort Necessity, which helped to instigate the Seven Years’ War. Taken hostage to ensure British compliance with the 1754 battle’s surrender terms, Stobo had spent almost five years in Quebec City and knew the area well. After escaping, he joined Wolfe for the siege.8

Whatever the source of Wolfe’s information, on 10 September he was able to discern four important facts about the Anse au Foulon:

• A path led up the steep cliffs just to the left of the cove.

• Ebbing tides created a vast beach suitable for landing craft and organizing troops.

• Sentries guarded the top of the path but not its foot at the beach.

• The sentries could not see down to the beach in daylight, let alone at night, because the cliff was treed, and they likely could not hear what was happening on the beach because of noise from the ebbing tide.

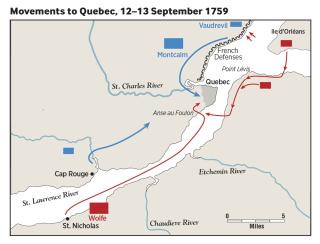

The Amphibious Operation

To deceive the French as to Wolfe’s intentions, Vice Admiral Saunders with the bulk of the British fleet staged a feint on 12–13 September against the French lines downriver from Quebec. As boats were rowed between Beauport and the St. Charles River, the Pembroke set up a diversion by laying markers to the shore as though to guide landing craft. Ships began to signal, fire guns at the French trenches, and sail close to land as if about to attack. A skeleton force in the British camp opposite Quebec beat drums and lit fires as if preparing to cross the river and attack. The ruse worked, keeping Montcalm, who was at Beauport, and the bulk of his troops up all night anticipating an attack that never came.

Miles upriver, just beyond Cap Rouge, 3,000 soldiers mustered around the 50-gun HMS Sutherland. Another 1,200 troops had moved from their Point Lévis and Île d’Orléans camps to a point across the river from the Foulon path. At 2200 on 12 September, 1,800 soldiers began embarking aboard small armed sloops, while another 1,800 descended into 30 landing craft and ships’ boats alongside the Sutherland, which hid them from French observers. A few of the landing craft were rowed upstream with the tide, so as to mislead any sentries around Cap Rouge.

Then, around 0200 on the 13th, the Sutherland hoisted two lanterns as a signal for the convoy of 30 craft to start, and the boats, commanded by Captain Chads and arrayed in a long line, set out with the ebbing tide on the approximately 10-mile trip to the Anse au Foulon. A half-hour later, the flotilla of sloops would follow Chads’ landing craft down the river.

Rear Admiral Holmes would accompany the third convoy of vessels, which carried the second wave of British troops and would set out at about 0330. He later reported, “I got underway in the [28-gun frigate] Lowestoff, and had with me the [24-gun frigate] Sea Horse, [20-gun post ship] Squirrel, & Hunter Sloop, and two Transports, all full of Troops.”9

British observers had seen French supply boats being loaded upriver and informed Wolfe that the vessels would run down with the tide to Quebec on the night of 12–13 September. French deserters confirmed the information. One of the reasons Wolfe chose that night to move his troops was because hungry French sentries along the route would believe the landing craft were the supply boats. Ironically, the supply foray was canceled, a fact neither Wolfe, nor the sentries, nor Montcalm, nor Bougainville knew.

HMS Hunter was anchored about two miles west of Foulon to help Chads navigate, but the sloop’s captain, thinking the landing craft were the French supply boats, almost fired on them. Wolfe had kept his plans from virtually everyone. Contrary to myth, Wolfe, in one of the craft, did not recite poetry during the trip downriver, and French sentries along the cliffs above the St. Lawrence were not negligent.

Captain Simon Fraser, a French-speaking former Scots mercenary, was in the lead craft. When French sentries at Sillery and the Samos Battery called out challenges as his boat slipped past, he replied in French for them to be quiet. Eventually, the sentries on the shore realized the boats were British and opened fire on the flotilla of sloops.

In an insightful after-battle report, Rear Admiral Holmes succinctly summarized the complex naval operation:

The Care of landing the Troops & sustaining them by the Ships, fell to my share—The most hazardous & difficult Task I was ever engaged in—For the distance of the landing place; the impetuosity of the Tide; the darkness of the Night—& the great Chance of exactly hitting the very spot intended, without discovery or alarm, made the whole extremely difficult.10

The Climb to the Plains

Lieutenant Colonel William Howe’s light infantry, in the first eight landing craft, began disembarking on the Foulon cove’s large beach around 0400. The current had carried the boats farther down the beach than intended, and Howe quickly led his three companies up the cliff but well to the east of the path. Among the climbing soldiers was Captain Donald MacDonald of the 78th Fraser Highlanders. MacDonald had been in the French Royal Scots and knew French military language and procedures intimately.11 Once at the top with eight of his men, he told alert sentries there in French that he had come from Quebec to relieve them.12 After attacking the bewildered guards and driving off their sleepy companions, the Highlanders gave a loud cheer. Soon Howe’s troops, after scaling the cliff, were advancing west, to silence the guns at Sillery and Samos.

By 0600, the landing craft had disembarked the second wave of troops. Climbing a cliff path in darkness or the dim light of early dawn is difficult, so a line of soldiers probably guided and hauled others up. The third wave from across the river was landed before 0700, and by around 0800, Wolfe was deploying his battalions on the Plains of Abraham, southwest of Quebec.

The speed with which Wolfe landed his troops, scaled the cliff, and positioned them created false assumptions among the French commanders. Governor General of New France Pierre de Vaudreuil, at the Beauport trenches, and Captain Jean-Baptiste de Ramezay, commander of the Quebec City Guards, did not believe the British could have placed such a large and coordinated force just outside the fortress so quickly. They assumed the soldiers on the Plains of Abraham were a diversion. Consequently, they prevented their approximately 2,500 men from joining Montcalm for the final battle on the Plains.

Montcalm believed that the guns firing at 0500 were British, aiming at the supply boats. In fact, they were French cannon at Sillery firing at Wolfe’s sloops. Montcalm later assumed Bougainville knew by about 0600 that the British forces were on the Plains. In fact, the sentries at Foulon and Samos had fled to Quebec, not toward Cap Rouge; there, Bougainville assumed Wolfe was still upriver. Montcalm’s message to Bougainville ordering him to march to the Plains reached him at 0900, approximately one hour before the battle. Wolfe’s speed had prevented the bulk of Bougainville’s men from joining the fight.

Prelude to Battle

The Plains of Abraham is a series of ridges edged by precipitous escarpments 180 feet down to the St. Lawrence and St. Charles rivers. The undulating tabletop about 1,000 yards wide was not the flat area its name implies. Wolfe deployed his troops in a line two men deep across the heights on one of the steepest ridges. Geographic features would dictate the nature and course of this battle.13 Rear Admiral Holmes would write that “the inequalities of the Ground, covered numbers of our Men, & kept him [Montcalm] from forming a just opinion of their Strength.”14

Wolfe’s deployment of his army in a defensive position on the ridge with both flanks protected by abrupt escarpments created huge problems for Montcalm. For the first time in the campaign, the French were the attackers, a role for which they had neither planned nor trained. The dispersed French forces were unable to coordinate an attack because the terrain made communications difficult. Montcalm has been criticized severely for attacking Wolfe around 1000, before Bougainville had arrived. But the general had realized that the Royal Navy would be moving even more artillery up the cliffs than the two 6-pounders supporting Wolfe’s line, and his army could not attack uphill against massed muskets and more cannon.15

In addition, Montcalm’s men, in anticipation of an attack under the cover of darkness, had not slept the previous night and then had to force march the seven or eight miles from the trenches at Beauport to the battlefield. In contrast, Wolfe’s men were rowed to Foulon and then slept for an hour or more on the Plains prior to the fight.

A Brief, Consequential Fight

As the French prepared to advance, the British battalions, two men deep, stood firm and silent along their ridge, their muskets loaded with two balls for greater impact. Across the field, Montcalm rode the length of his line, arrayed in three columns, waving his hat to generate enthusiasm and signal the start the attack.16

The five regiments of regular troops at the center of the French line had been padded out with militiamen, and the formations soon would lose cohesion. The militiamen, having no bayonets, threw themselves to the ground and fired before they had reached the killing range of 18th-century muskets. As a result, the British ranks were subjected to only light fire.17 The French regulars had to leap over the prone militiamen to advance, diminishing the charge’s cohesion. The attackers were tiring by the time they had waded through cornfields and uneven terrain to reach the foot of the British ridge.

In contrast, the well-coordinated British redcoats on the higher ground waited until the French were within the 50-yard kill zone to fire their double-shotted volleys. They did not fire only one thunderous volley but several, each with devastating results on the enemy soldiers struggling uphill on wet grass. British diarists made clear that the redcoats “continued firing very hot for about six (or as some say) eight minutes.”18 Consequently, the British fired a minimum of 4,000 musket balls, and possibly as many as 25,000, down into the nearby French. Their fusillades transformed the French from enthousiaste to paniqué.19

After 15 minutes of firing, the French survivors fled back to their starting ridge, pursued by the fresher British troops. French regulars would blame defeat on the ill-trained militia and irregulars for not holding their ground.20 Wolfe was mortally wounded as the British line began advancing on the retreating French and lived just long enough to be told that he had won. The 78th Fraser Highlanders, wielding claymores—Scottish broadswords—ferociously charged downhill into a tired, retreating French force. They probably killed several hundred men, as they claimed. Given the number of musket balls fired at close range and the effects of a sword charge downhill into a panicked army, it is highly doubtful that both sides suffered the same approximate casualty rate, as many modern Canadian historians claim. Montcalm was mortally wounded, probably by grapeshot fired by a British cannon, while trying to rally his soldiers.

The militiamen fled the battlefield to the brush along the cliff tops, but the precipices, so effective in keeping the British out, now effectively kept the French in. On the northern edge of the Plains, amid rugged, wooded terrain, many held out for a time before they were trapped and then killed by the 78th Frasers and 58th and 2nd Royal Americans. The nuns in the convent hospital below looked up to describe the fight as “a massacre of French-Canadians” and were “Surrounded by hundreds of the dead and dying . . . many of whom were our close relatives.”21

The British suffered 42 dead on the day of the battle and a further 16 later from their wounds. Many Canadian historians maintain that the militia inflicted great casualties on the 78th Frasers in the woods overlooking the hospital. But only 18 of the Highlanders were killed in the entire battle.

Appropriately, Vice Admiral Saunders, the overall naval commander, cosigned the Quebec surrender documents a few days after the battle. In his report to the Secretary of the Admiralty, he noted, “I have the pleasure also of acquainting their Lordships that during the tedious campaign, there has continued a perfect good understanding between the army and Navy.”22

Postscript to the Battle

The withdrawal of Royal Navy ships before the winter freeze meant that Quebec City was a British outpost surrounded by hostile forces for hundreds of miles upriver and downriver. The following spring, the French in Montreal mustered a large force that defeated British Brigadier General James Murray at the 28 April 1760 Battle of Sainte-Foy. Murray and his surviving men fell back behind Quebec’s fortifications. He feared French warships would sail up the river to recapture the city, not realizing that the Royal Navy had destroyed the French fleet at the Battle Quiberon Bay near St. Nazaire on 20 November 1759 (see “The Trafalgar of the Seven Years’ War,” June 2020, pp. 28–33).23 Nevertheless, by ignoring the naval side of the struggle for Quebec, many historians have assumed Murray’s fears to be true and falsely believed the fortress city could have been retaken.

“Wooden walls” defeated the “stone walls” (forts) guarding New France from Quebec City to New Orleans. Wolfe’s “Manoeuvrist Approach” had relied on shock, deception, and surprise to deceive, divide, and defeat a larger French army.24 The striking power of Wolfe’s army was disproportionate to its size and explains the capture of a fortress protected by rivers, cliffs, and thousands of defenders in the heart of enemy territory.

The accomplishment of a comparatively small force led directly to the largest land transfer in history, and British military expenditure for approximately the next one and a half centuries would fund a large navy to support a small, successful army.25

1. Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (New York: Collier Books, 1966), 522.

2. Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Quebec (Toronto: William Collins Sons & Co., 1972), 94–98.

3. Warner, With Wolfe to Quebec, 117; C. P. Stacey, Quebec, 1759: The Siege and the Battle (Montmagny, Quebec: Marquis Imprimeur, 2002, rev. ed.), 75.

4. Sam Allison, Driv’n by Fortune: The Scots’ March to Modernity in America 1745–1812 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2015), 101, 109–13.

5. Warner, With Wolfe to Quebec, 125–27.

6. D. Peter MacLeod, Northern Armageddon: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Making of the American Revolution (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntire, 2008), 140.

7. Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of the Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), 352.

8. Robert C. Alberts, The Most Extraordinary Adventures of Major Robert Stobo (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1965), 79–84, 257–59.

9. MacLeod, Northern Armageddon, 143–44; Report by Rear-Admiral Charles Holmes, 18 September 1759.

10. Holmes, Report.

11. MacLeod, Northern Armageddon, 146–47, 151–52; Allison, Driv’n By Fortune, 113.

12. Pierre Pouchot, Memoirs on the Late War in North America Between France and England (Youngstown, NY: Old Fort Niagara Association, 2004), 254–56.

13. John Keegan, Warpaths: Travels of a Military Historian in North America (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1995), 135–36.

14. Holmes, Report.

15. Brian Connel, The Plains of Abraham (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1959), 55.

16. MacLeod, Northern Armageddon, 182–83.

17. Stephen Brumwell, Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755–1763 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 249–50.

8. Allison, Driv’n By Fortune, 121.

9. John Keegan, Warpaths: Fields of Battle in Canada and America (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1996), 128–29.

20. Pouchot, Memoirs on the Late War, 256.

21. Nun of the General Hospital of Quebec, “Narratives of the Doings During the Siege of Quebec, and the Conquest of Canada, in 1759” (Quebec City: Quebec Mercury Office, 1855 [?]).

22. Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders to Secretary of the Admiralty John Clevland, 21 September 1759, quoted in Barry Gough, “Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Saunders, Naval Victor of Quebec 1759,” The Northern Mariner 19, no. 1 (January 2009): 20.

23. N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815 (London: Penguin Books, 2005), 282.

24. Andy Young, “Developing Amphibious Doctrine: The British Experience of the Seven Years’ War,” 4.

25. Alexander Campbell, The Royal American Regiment and Atlantic Microcosm, 1755–1772 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 109.