This summer our country celebrated the 75th anniversary of our victory over Imperial Japan during World War II. Just this week, on 2 September, we remembered the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender from the deck of the USS Missouri (BB-63), formally bringing the hostilities of World War II to an end. For most of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, it was time to come home.

Nearly every week, local news outlets in Norfolk, San Diego, Jacksonville, Bremerton, Pearl Harbor, and elsewhere remind the public of the comings and goings of the nation’s warships. “Carrier Eisenhower Returns From Deployment After Spending Almost 7 Months at Sea” and “Navy helicopter Squadron Returns Home from 7-month Deployment” are two recent examples. News broadcasts and viral social media videos of sailors reuniting pierside with loved ones never fail to warm hearts and instill a sense of pride in the brave men and women who go to sea on our behalf to fight and win the nation’s wars. Need a breath of fresh air from the toxic social media environment? Just watch a few Navy homecoming videos on YouTube to restore your faith in humanity.

The voyage home, however, likely began weeks prior, and for those who have never been to sea with the U.S. Navy, it may be hard to understand the complex emotions of returning from deployment. A year of maintenance and predeployment workups, months at sea—often in the conduct of major combat operations, but more frequently in the endless hours of standing a professional watch—and then finally the order comes to point the bow towards home. Behind every official Navy report of a ship triumphantly returning from arduous duty are the thousands of personal stories resident in each sailor.

—–

James Edgar Wilson Sr. was 19 years old when the war against Japan ended on 15 August, 1945. On the signal bridge of the USS Randolph (CV-15), Signalman Second Class (SM2) Wilson spent a long, hot year supporting the fight against the Japanese. His war cruise would take him halfway around the world and back as part of the most powerful Navy ever assembled. After leaving San Francisco in January 1945, the Randolph immediately saw action as part of Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58), striking targets in mainland Japan just 21 days after weighing anchor in home waters. The Randolph went on to directly support the amphibious assaults against Iwo Jima, providing close-air support and reconnaissance for Marines engaged in the fight of their lives.

Later, on 11 March, at anchor near Ulithi, while 200 sailors were watching a movie in the hangar bay, a kamikaze plane flew more than 1,500 miles one way to strike the Randolph on the starboard side aft, just below the flight deck. Twenty-seven sailors died, presumably some of SM2 Wilson’s close friends and all of them shipmates, although years later he would never mention any details from that event with his own children or grandchildren. The fire and the damage control response was undoubtedly an intense and physically draining evolution for those involved. The effort worked thanks to the legendary hard work of her sailors, and the Randolph put back to sea in just a few weeks. She joined the assault on Okinawa on 1 April, supporting requirements for near-constant close-air support of Marines during the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific theater.

The pace of flight operations from the deck of the Randolph was relentless. For those that have experienced it in the modern Navy, it is easy to recall the physical and mental toll a day spent on a carrier flight deck under a harsh summer sun takes on the body. To transmit and receive orders, SM2 Wilson surely spent many hours flashing the signal lamp or hoisting signal flags to keep the fleet in tight formation that spring in 1945. He and his shipmates endured hours of grueling work each day, eager to take the strain for each other, for their ship, and for their country.

Joining Third Fleet in the summer of 1945, planes from the Randolph bombed targets up and down Japan. From several decks above the flight deck, SM2 Wilson had a bird’s eye view of the actualization of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s famous dictum to “hit hard, hit fast, hit often.” Aircraft launched from the deck of the Randolph struck targets near Tokyo right up through the morning of 15 August, when Emperor Hirohito broadcast Japan’s acceptance of the terms of surrender found in the Potsdam Declaration. I often imagine that while Ensign So-and-So in the radio room of the Randolph prepared the formal message for the captain, SM2 Wilson was busy making his way through the smoke pits, crew mess, and berthing areas passing word that the war was over. There certainly must have been cheers and joyous outbursts at the sudden announcement of peace.

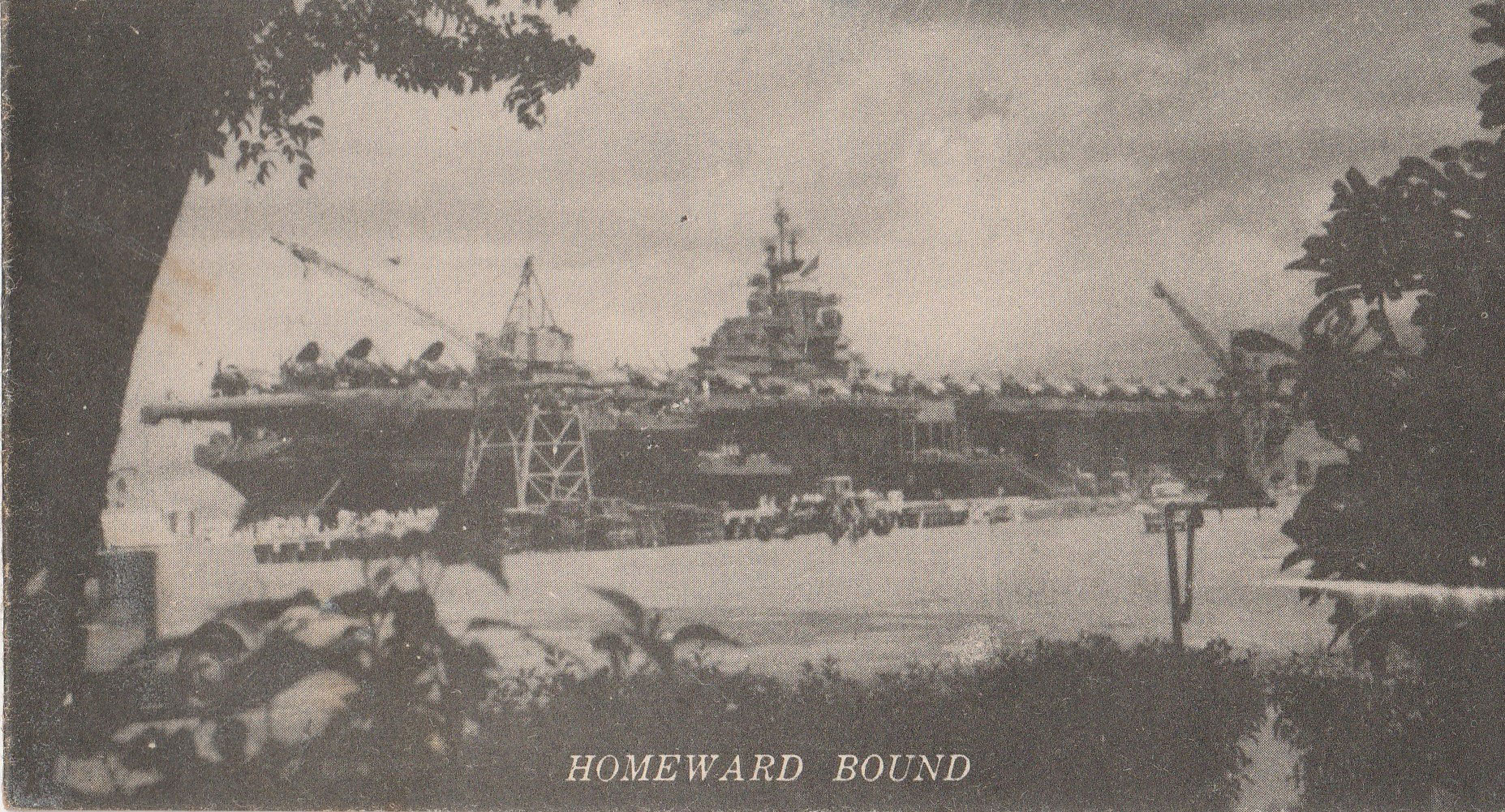

It is unclear from SM2 Wilson’s recounting if the Randolph flew the homeward bound pennant on 5 September 1945. Prescribed by Navy regulation, “a ship which has been on duty outside the limits of the United States continuously for a period of nine months (270 days) or more may fly the homeward bound pennant upon getting underway to proceed to a port of the United States.” Perhaps the signal shop on board the Randolph spent days excitedly preparing a pennant whose length would have exceeded 3,000 feet if constructed according to tradition—one foot of length for every officer and sailor who made the voyage. The flag would have been divided up equally among the crew upon returning to homeport, the portion near the hoist featuring a white star on a blue field would be presented to the captain. If such a flag was flown on the Randolph, and a portion of the red-over-white pennant given to SM2 Wilson, it has been lost to time. In the most likely event, SM2 Wilson hit his canvas rack that night on 5 September knowing, at long last, that the war was over and he was headed home.

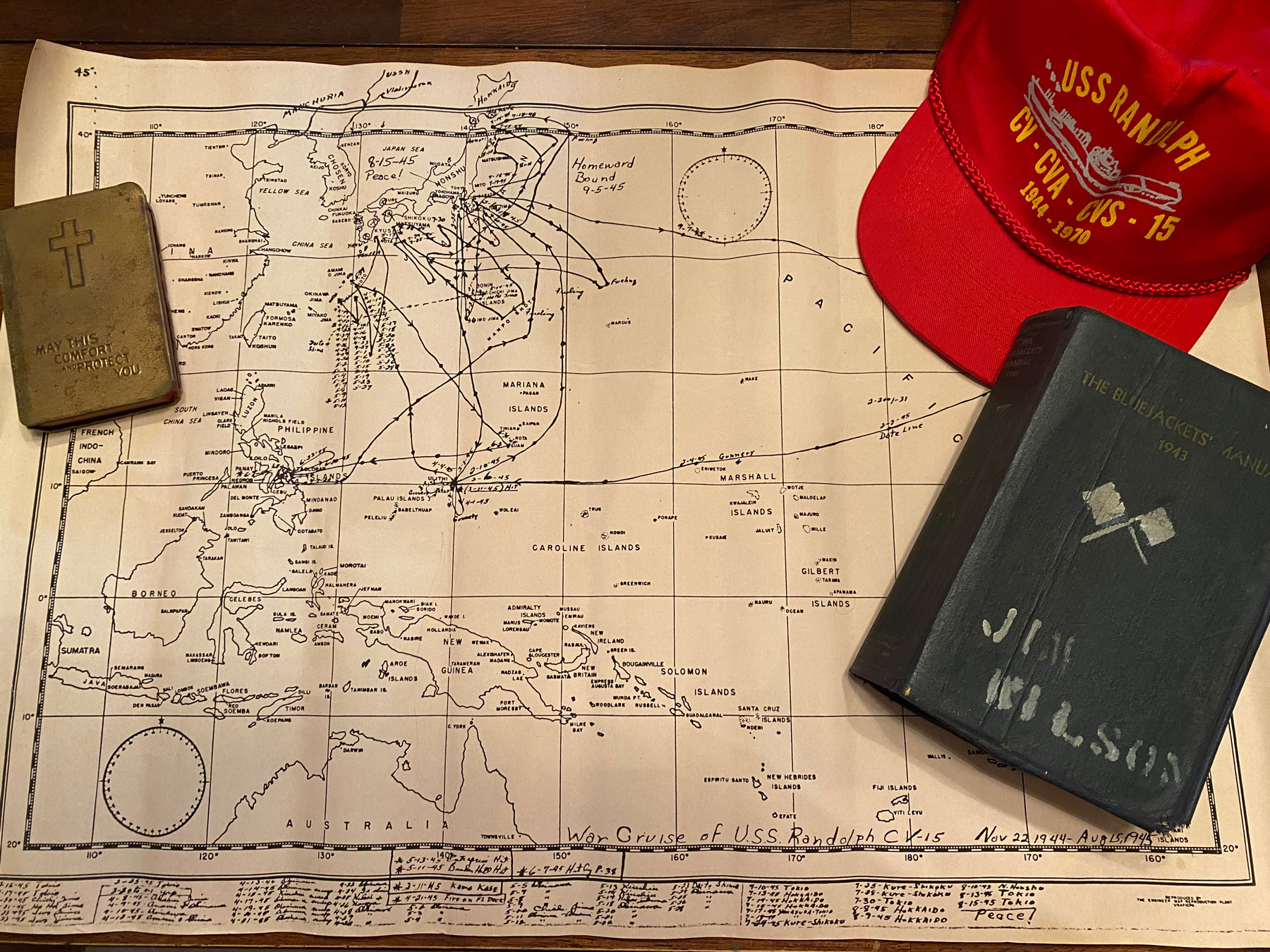

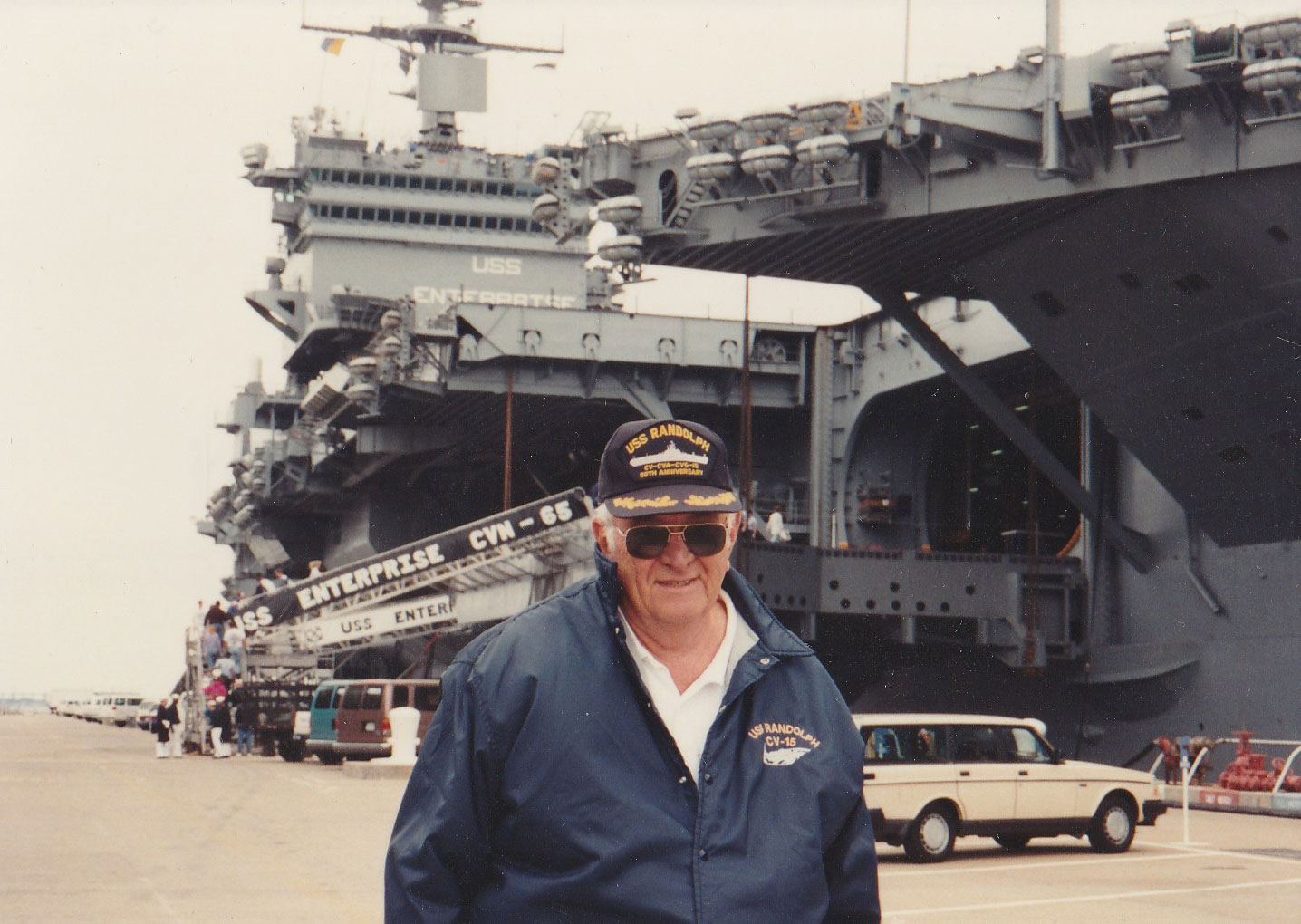

I never heard my grandfather’s Navy stories firsthand. He left a cruise box full of primary sources behind from which to infer the nature of his service—the Bluejacket Manual, a hand-drawn chart of his wartime cruise, a mesh ball cap with silhouette of an aircraft carrier, his uniform, hundreds of documents and pictures. They are among my most prized possessions. He assuredly was proud to have served, and I am proud to share his story here. It is a small, but worthy tale of our shared naval heritage, the fighting spirit of the Navy, and those who have gone before us to defend freedom and democracy around the world. To the Pacific sailors of World War II whose legacy we inherited, thank you. Seventy-five years later, I think you would be really proud of the men and women in today’s Navy. To the sailors afloat now, working diligently in far-off deployed locations—thank you, and here’s wishing you a happy voyage home.

No comments:

Post a Comment

How did you like the post, leave a comment. I would appreciate hearing from you all. Best wishes from JC's Naval, Maritime and Military News